China’s emergence as a global manufacturing superpower hinders European machinery production recovery.

How it all began

Nietzsche famously said, “Was mich nicht umbringt macht mich stärker" (“what doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger”). A saying that can be applied to China’s resilience and dominance as the world’s factory.

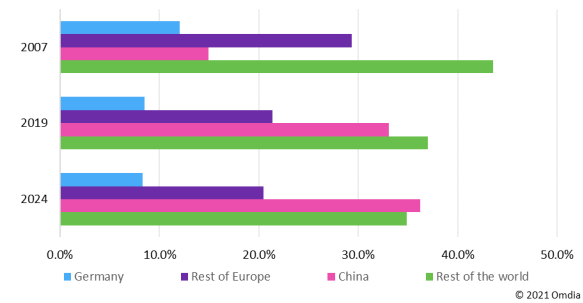

However, it was not always like this. China’s emergence as a global manufacturing superpower coincided with the third industrial revolution, with its position as a leading player in machinery manufacturing growing significantly over the last 15 years. In this time, China’s share of global machinery production has increased from around a tenth to one third.

This growth relied heavily on export markets, with China using its strength in low-cost manufacturing to encourage foreign direct investments in the country. Additionally, the Chinese government has prioritized investments in infrastructure, designed to encourage high rates of urbanization as it looks to move from primary to secondary and tertiary economic models.

As measured by industrial capex, which globally stood at US$4.1 trillion in 2019, China dominates and accounts for more than 45% of the total. China is followed by the US (16%), Japan (5%), India (2.5%), and Germany (2.5%)—although the European Union (EU) makes up approximately 12%. As such, this indicates that investments are still abundant in China and considerably higher than in other nations, suggesting that the country’s growth momentum will continue soon. Consequently, China’s global share of machinery production is likely to continue to increase.

However, China has been moving away from the high-growth model of the past to a more sustainable growth model focused on enhancing internal markets and becoming a world leader in emerging technology.

Machinery production, 2007–24

Source: Omdia

What triggered China to take on a new path?

Two words, trade war. Following the country’s long-term success in using low-cost manufacturing methods, the trade conflict between the US and mainland China highlighted the reliance many Chinese technology companies had on western suppliers, particularly for high-tech components. Subsequently, this indirectly pushed the country to be more independent in how it uses foreign support and technology in its manufacturing process and encouraged local companies to develop competing technology.

Additionally, there is a global shift in the manufacturing landscape, as many companies actively seek to lessen their supply chain reliance on China. Although there is little hard data to determine the level of reshoring, overseas companies are certainly moving away from manufacturing in China. According to Kearney’s China Diversification Index, China’s share in US import value from Asia declined from 67% in the first quarter of 2018 (1Q 2018) to 56% in the fourth quarter of 2019 (4Q 2019), roughly $31 billion of lost import value. The main beneficiary from the shift away from China is Vietnam, which absorbed almost 50% of the share. Vietnam exported an additional $14 billion to the US in 2019, compared to 2018.

While some surveys suggest that most US companies in China has no plans to relocate their production and supply chain from China to elsewhere, Omdia believes that the reshoring will be inevitable in the long term. The shift from China to other Asian countries has already happened and will continue. For the industrial markets, the effect of reshoring might take more time to take place as the market is more price-conscious.

A new home for low-cost, high-volume manufacturing

Many manufacturers are looking for the “next China.” That place is Southeast Asia, with Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia as prime candidates. Although Southeast Asia has had higher infection rates than China, it has not fallen behind in terms of manufacturing. While China was idle, sister plants in Southeast Asia took up the heaviest lifting manufacturing. As a result, manufacturing activities were cranked up to meet demand.

Local governments are also giving large incentives to keep the momentum going after the dust settles. All is looking good for Southeast Asia, but expectations need to be set, as it is almost impossible to replace all the workload from China. Southeast Asia does not have the capacity, infrastructure, or talent to directly take low-cost manufacturing away from China, at least in the short to midterm.

Globally, Southeast Asia is not a major machinery producer, but it is a big machinery user. Indirectly, COVID-19 has presented a test to Southeast Asia—if the region can take more manufacturing capacity. There is a slow but sure shift of manufacturing moving from China to elsewhere in Asia & Oceania, and the current focus is Southeast Asia.

COVID-19: Giving China the upper hand

When COVID-19 was rampant in China, major lockdowns were the only way to contain the disease. Consequently, that triggered a domino effect around the world by cutting off major manufacturing supply chains. This, along with the preference in China to supply Chinese manufacturers with parts first, created an artificial lag that extended part shortages and lead times. Looking back to 2020, this has hindered the European machinery and manufacturing landscape, but China came out of it almost unharmed as it became the fastest-recovering country. Omdia projects China will continue to be the fastest-recovering country in the latter half of 2021, pushing machinery sales in Asia into the low single-digit growth.

The main benefit for Chinese machinery producers is that the impact of COVID-19 has made companies across the world more cost-conscious. Increased transportation costs hit profit margins, while a lack of downstream demand reduced revenues. As a result, many capital and operational budgets have been reduced. This has encouraged those companies looking to invest in new machinery to broaden their range of potential partners, increasing opportunities for Chinese vendors while introducing more competition to previously difficult to penetrate markets like Europe.

What about the stigma behind China-made goods?

In recent years, China has moved away from the image of making low-cost, high-volume products with questionable quality. Increasing legislative and environmental standards, as well as a desire to be a world leader in emerging technology, has driven China to shift manufacturing focus towards high-quality products with an affordable price tag. Thus, China is now producing higher-quality machinery at a lower cost than its European counterparts. Quality and price may be subjective, but by doing so, China has indirectly challenged the EU’s machinery production market.

In Germany, manufacturers typically only use locally made machinery as the quality standards are generally higher, and brand loyalty plays a big part in machinery purchases. In the past, there was also a substantial language barrier, but since new machinery is now operated with user interfaces (UIs), the barriers to entry, learning, and training have shrunk. There is a growing trend of European manufacturers inquiring about China-made machinery, with many opting to use Chinese products in their plants. They provide similar quality at a fraction of the price.

This is the same story that was seen in the automotive industry over a decade ago, whereby there was a lot of criticism when Porsche and Ducati were building their products in China. These brands, synonymous with quality and performance, were expected to fail because of the low-quality of Chinese manufacturing. However, those brands expanded because the cost to quality ratio was very high. Fast forward a few years and that stigma is practically gone; it does not matter where the product is being manufactured.

This scenario extends further to Chinese ownership, such as in the case of Volvo. With the Ford Motor Company at the brink of ruin, the Volvo Cars quickly found itself sold for $1.8 billion to the highest bidder—billionaire Li Shufu—in the largest overseas acquisition by a Chinese automaker, Geely. Following a refocus of Volvo's product line under Geely, the carmaker revived sales in Europe, the US, and China. The brand has since moved upmarket to compete against the likes of Daimler's Mercedes-Benz and BMW. The dubious partnership that many had questioned has become an automotive success story.

Summary

Overall, China has recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic better than Europe and the rest of the world, giving it a unique opportunity to increase its market presence in previously hard to penetrate markets. Machinery buyers are interested in quality, cost, and delivery, with Chinese vendors being able to satisfy all three requirements. Omdia is not painting a doomsday scenario for the German and European machinery markets. Omdia is merely identifying the challenges that European machine builders will face in the near term and the long term as China looks to move away from low-cost manufacturing to become a world leader in machinery and emerging technology.

Appendix

Further reading

Lisa Wang, Biden Election Win – Will It Make Any Difference? (December 2020)

Joanne Goh and Peter Taylor, Manufacturing technology – Trends to watch in 2021 (January 2021)

Author

Teik Chuan Goh, Research Analyst, Manufacturing Technology

Peter Taylor, Research Manager, Manufacturing Technology